Those acts of kindness are prominent as Carol describes the legacy of the man she was married to for 44 years. Barry died in 2014 after a four-year fight with Lewy body dementia. The disease was devastating to Barry, an Air Force veteran who served in Vietnam.

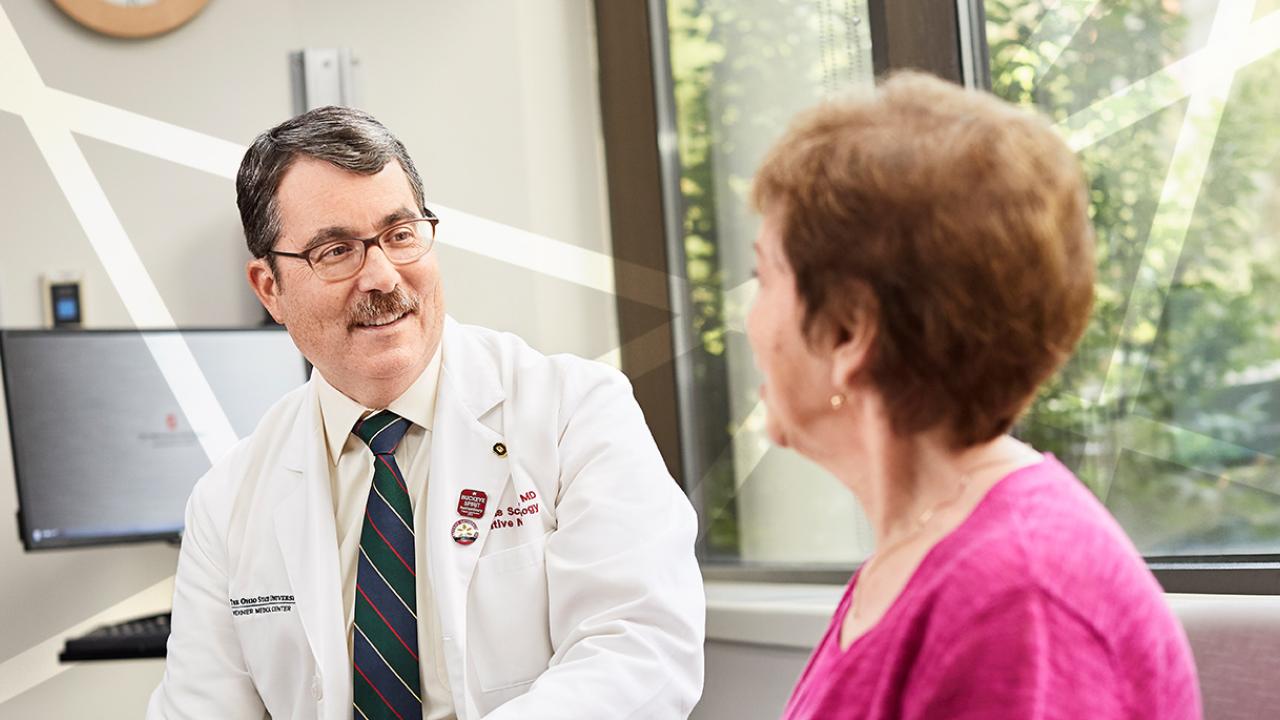

He saw five neurologists before he came to Ohio State and met with Douglas Scharre, MD, director of the Division of Cognitive Neurology.

“Dr. Scharre is such a wonderful man, and so knowledgeable about all dementias, but especially Lewy body,” Carol says. “He prescribed treatment, but the big thing was that when we left there, Barry said ‘Finally, somebody gets me.’”

Barry retained his memory, but his ability to respond to questions began to decline. Eventually his voice weakened to the point he could not speak, and his physical capabilities eroded to the point that he was bedridden.

“This affected his whole life. He never got to the point where he accepted the diagnosis,” Carol says.

With the help of a philanthropic investment from the Mangurian Foundation, Dr. Scharre is playing a key role in helping find better treatments and outcomes for Lewy body dementia patients like Barry.

Dr. Scharre is leading a research team that is working on a three-part approach to studying Lewy body dementia. The first component was to develop a clinical profile for Lewy body dementia patients. The disease is often misdiagnosed as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease. Lewy bodies, collections of proteins (alpha-synuclein) that accumulate abnormally in the brain, are not typically seen in Alzheimer’s and are deposited in different parts of the brain than in Parkinson’s.

“It’s vitally important that patients are correctly diagnosed so that they can be prescribed the proper medications that may help slow down the course of the disease or improve symptoms,” Scharre said.

Dr. Scharre has been instrumental in helping with early diagnosis for cognitive decline. In recent years, he developed a simple test, called SAGE (Self-Administered Gerocognitive Exam). SAGE, which a patient can take at home in about 15 minutes with a pen and paper, can reveal signs of memory, cognitive or thinking impairments that patients were unaware they had.

“If we see this change, we can catch it really early, and we can start treatments much earlier than we did without a test,” Dr. Scharre says.

These advancements can have a monumental impact. Worldwide, about 50 million people suffer from dementia, and about 10 million more cases are diagnosed each year, according to the World Health Organization. At a given time, up to 8 percent of people ages 60 and older have dementia.

The second portion of the team’s research, which is currently underway, is to use neuroimaging to study the link between sleep abnormalities and dementia. Dr. Scharre also intends to study biomarkers for the disease as a future project, the third focus area of his research.

The Pfaffs have also helped to carry on Barry’s legacy by helping to raise money for Dr. Scharre’s research. Carol and her two sons have held three fundraising events to date, and they’re planning a golf outing for next year — a meaningful tribute to Barry, who loved golf.

“If I can alleviate the pain that we’ve had for one family, it would be worth all we’re doing,” Carol says.